IKORO

The ikoro, located at the center of the village square (ogo), was both a symbol and public platform for the performance of ndi ikike masculinity. It is a wooden “slit-drum of great size used to summon the able-bodied members of the village in times of serious emergencies. Until the early 20th century, before effective British colonialism and the entrenchment of Christianity, when the ikoro was sounded, only men came out. The role of beating the ikoro was fulfilled by an indiviudal who had accomplished masculinity. He was known as ezie-ikoro (priest/master of the ikoro).Various male age-grades (uke) took turns keeping watch over the ikoro, because it represented the strength of a community.

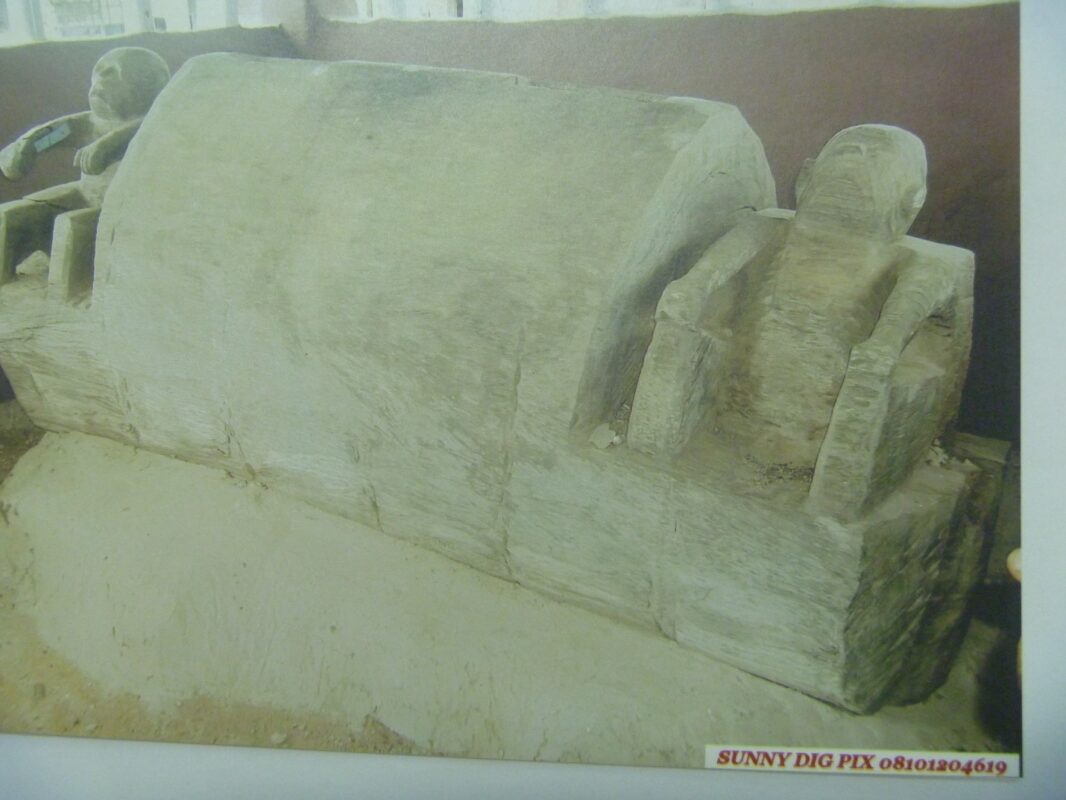

The notion of the ikoro as signifying a community’s strength is informed by the arduous labor involved in its creation, as well as its ritual transformation into a protective medicine. The making of the ikoro involved the collective labor of all able-bodied adult males in a community, who took turns cutting down the huge tree required for the ikoro drum, and hauling it back to the village-square amidst jubilations. Special wood carvers then set to work hollowing out the tree trunk and designing the ikoro, over a period of about six months. Upon completion, the ikoro drum usually stood at nine feet in length, five feet in height, and about seven to ten feet in circumference. Before the ikoro could be used, human heads were sacrificed to it to transform it into a protective medicine. Ikoro was a public platform for the performance of iba mba (warrior’s boast)

After a successful human headhunt, there was always an elaborate ceremony where the [warrior] would display the head. He would then be qualified to be welcomed by the village tom (ikoro), a victory war drum, which he in turn would salute (ibiri ikoro) in a display of gallantry of his prowess in war.

Upon a warrior’s return from war in the 19th century, “half-running, half-walking,” he trotted to the village-square in front of the “talking ikoro,” where “holding his trophy [human head] proudly aloft,” he saluted it, and performed the warrior’s boast. The moment before the ikoro was one of ecstasy and grief; jubilation for those whose loved one returned in triumph, and sorrow for those whose relation failed to return or cut a human head. It was a moment of social distinction between Ndi Ikom( real men) and ujo (the scared). Once the ikoro had sounded, everybody would shout, ‘yooooooo! uma-moo, uma-moo!’ As the shouts rent the air, his wife would emerge with nzu [white chalk] to decorate and venerate him publicly. Other women would then join her in dancing and jubilation. During festivals such as the celebration of the new yam, the entire community assembled at the village-square, and as people made their entrance, the ezie-ikoro (priest/master of the ikoro) drummed praise beats for the ufiem and insolent beats for the ujo.

When the ikoro saw you wearing a jooji wrapper, it would ask you, ‘Gu o gbuu ole ndu were uko turu isi?’ [‘Which people have you killed to provide skulls for your hearth?’] If you failed to understand the ikoro or ignored it, it would then insult you, saying, ‘O di gologolo pu!’ This means, ‘There goes an empty and weak male! He is no man!’ If you understood the ikoro, you would perform the warrior’s boast [iba mba] before it, informing the ezie-ikoro of your recent igbu ishi accomplishment. Real men would be lying down in his house, listening to the beats of ikoro, and would laugh and say the ikoro is insulting so and so person. When they went to the village-square, the ikoro hailed them ‘O-mere-ndi–a-duyi-mweyi-okpa!’ [‘the terror of the shoe-wearers’]; ‘Ishi-e-bu-ite-ndi-una!’ [‘the head that carries the pot of the braves’] — that is the leader of the ite odo society; ‘O-mere-ndi-na-ata-mgba-mgba’ [‘the terror of Ibibio people.’]

From the foregoing, it is clear that ibiri ikoro (to salute the ikoro) and iba mba (the warrior’s boast) were mundane practices in the 19th century; an embodied consciousness (a habitus), a celebration of ufiem, a denunciation of ujo, and a memorialization of heroic ancestors.

The ikoro, located at the center of the village square (ogo), was both a symbol and public platform for the performance of ndi ikike masculinity. It is a wooden “slit-drum of great size used to summon the able-bodied members of the village in times of serious emergencies. Until the early 20th century, before effective British colonialism and the entrenchment of Christianity, when the ikoro was sounded, only men came out. The role of beating the ikoro was fulfilled by an indiviudal who had accomplished masculinity. He was known as ezie-ikoro (priest/master of the ikoro).Various male age-grades (uke) took turns keeping watch over the ikoro, because it represented the strength of a community.

The notion of the ikoro as signifying a community’s strength is informed by the arduous labor involved in its creation, as well as its ritual transformation into a protective medicine. The making of the ikoro involved the collective labor of all able-bodied adult males in a community, who took turns cutting down the huge tree required for the ikoro drum, and hauling it back to the village-square amidst jubilations. Special wood carvers then set to work hollowing out the tree trunk and designing the ikoro, over a period of about six months. Upon completion, the ikoro drum usually stood at nine feet in length, five feet in height, and about seven to ten feet in circumference. Before the ikoro could be used, human heads were sacrificed to it to transform it into a protective medicine. Ikoro was a public platform for the performance of iba mba (warrior’s boast)

After a successful human headhunt, there was always an elaborate ceremony where the [warrior] would display the head. He would then be qualified to be welcomed by the village tom (ikoro), a victory war drum, which he in turn would salute (ibiri ikoro) in a display of gallantry of his prowess in war.

Upon a warrior’s return from war in the 19th century, “half-running, half-walking,” he trotted to the village-square in front of the “talking ikoro,” where “holding his trophy [human head] proudly aloft,” he saluted it, and performed the warrior’s boast. The moment before the ikoro was one of ecstasy and grief; jubilation for those whose loved one returned in triumph, and sorrow for those whose relation failed to return or cut a human head. It was a moment of social distinction between Ndi Ikom( real men) and ujo (the scared). Once the ikoro had sounded, everybody would shout, ‘yooooooo! uma-moo, uma-moo!’ As the shouts rent the air, his wife would emerge with nzu [white chalk] to decorate and venerate him publicly. Other women would then join her in dancing and jubilation. During festivals such as the celebration of the new yam, the entire community assembled at the village-square, and as people made their entrance, the ezie-ikoro (priest/master of the ikoro) drummed praise beats for the ufiem and insolent beats for the ujo.

When the ikoro saw you wearing a jooji wrapper, it would ask you, ‘Gu o gbuu ole ndu were uko turu isi?’ [‘Which people have you killed to provide skulls for your hearth?’] If you failed to understand the ikoro or ignored it, it would then insult you, saying, ‘O di gologolo pu!’ This means, ‘There goes an empty and weak male! He is no man!’ If you understood the ikoro, you would perform the warrior’s boast [iba mba] before it, informing the ezie-ikoro of your recent igbu ishi accomplishment. Real men would be lying down in his house, listening to the beats of ikoro, and would laugh and say the ikoro is insulting so and so person. When they went to the village-square, the ikoro hailed them ‘O-mere-ndi–a-duyi-mweyi-okpa!’ [‘the terror of the shoe-wearers’]; ‘Ishi-e-bu-ite-ndi-una!’ [‘the head that carries the pot of the braves’] — that is the leader of the ite odo society; ‘O-mere-ndi-na-ata-mgba-mgba’ [‘the terror of Ibibio people.’]

From the foregoing, it is clear that ibiri ikoro (to salute the ikoro) and iba mba (the warrior’s boast) were mundane practices in the 19th century; an embodied consciousness (a habitus), a celebration of ufiem, a denunciation of ujo, and a memorialization of heroic ancestors.